The Field Museum in Chicago has covered up several display cases that feature Native American cultural items in response to new federal regulations that require museums to obtain consent from tribes before exhibiting objects connected to their heritage.

Museums across the country have been preparing for the new regulations, which go into effect on Friday, with officials consulting lawyers as curators scramble to read through rules that will influence staffing and budgets for years to come.

The federal government overhauled rules that were established in the 1990s, hoping to accelerate the repatriation of Native American remains and cultural patrimony — a process that tribal officials and repatriation advocates have long criticized for moving too slowly.

The Field Museum’s decision relates to a provision that requires institutions to “obtain free, prior and informed consent” from tribes before exhibiting cultural items or human remains, or allowing research of them. Museums have had to decide whether to leave Native objects on display and risk violating the new rules, or to remove the objects while engaging in what might be a lengthy process of requesting tribal consent.

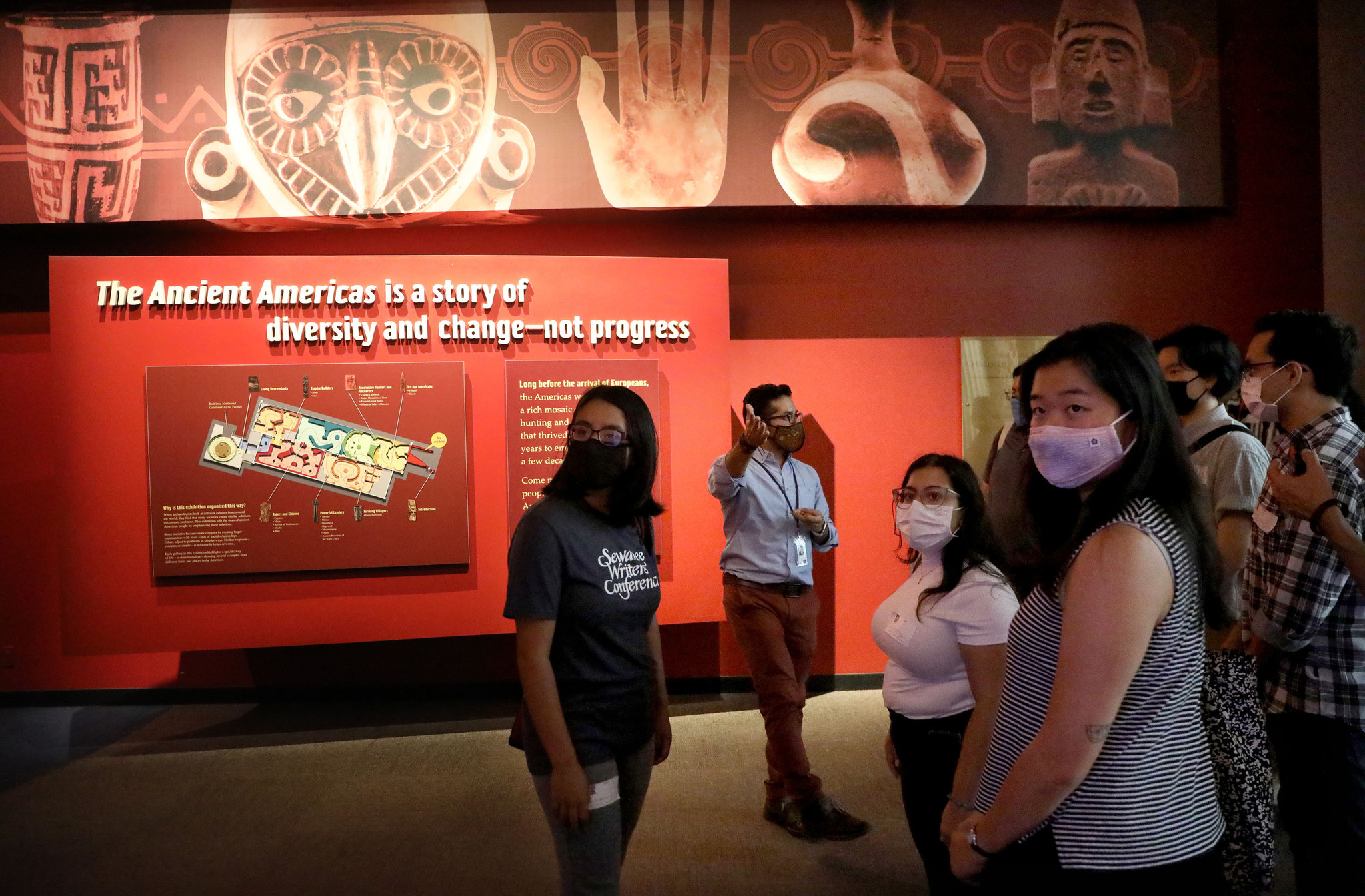

The decision by the Field Museum, which was announced this week on its website, applies to display cases in its halls of the ancient Americas, focused on civilizations in the Western Hemisphere spanning 13,000 years, and in a hall about 10 Native nations in the Pacific Northwest.

“Pending consultation with the represented communities, we have covered all cases that we believe contain cultural items that could be subject to these regulations,” said the museum, which noted it does not display human remains.

It was not immediately clear which items had been obscured and which tribes the museum was planning on consulting. Museum representatives did not immediately respond to requests for further information.

Many institutions that display Native American cultural items, including the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, have not announced how their exhibitions will be affected.

“It’s as clear as day,” said Shannon O’Loughlin, chief executive for the Association on American Indian Affairs, a nonprofit that assists Native nations and Indigenous people with repatriation. “They need to proactively fix it if they are out of compliance.”

Part of the newfound urgency around repatriation has been fueled by a broader effort at museums and universities to right historical wrongs. Holdings of Native American remains are often linked to grave robbing, archaeological excavation and development on burial grounds.

Another driver has been the Biden administration, which has been trying to find ways to accelerate the repatriation process since 2021. The remains of more than 96,000 Native American individuals continue to be held in institutions that include large museums and tiny local historical societies.

The new regulations end some practices that repatriation advocates said were responsible for delaying returns. Institutions can no longer label remains as “culturally unidentifiable,” a category that made it more difficult for tribes to make claims on those holdings.

Created in consultation with dozens of federally recognized Native American tribes, the new rules also seek to address long-standing concerns about how much consideration tribes are paid regarding exhibitions and research.

“If people were treating that relationship with respect in the first place, there probably wouldn’t be a need for the rule,” said Bryan Newland, the assistant secretary for Indian affairs and a former tribal president of the Bay Mills Indian Community.

Some leaders in the museum and archaeology worlds have argued that the new rules overstep and that museums should maintain autonomy in managing their collections. If a museum is accused of not following the federal regulations, which are administered by the Interior Department, the government can issue a fine.

The Field Museum, which was founded in 1894 after the World’s Columbian Exposition as a repository for items displayed at the fair, is among the museums that have renewed their commitments to repatriation in recent years. It has one of the largest collections of Native American remains, with holdings that represent more than 1,200 individuals, according to federal government data published in the fall.

c.2024 The New York Times Company